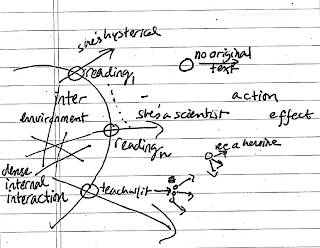

A quick mindmap to try to understand the interaction model.

Foote, Bonnie. “The Narrative Interactions of Silent Spring: Bridging Literary Criticism and Ecocriticism.” New Literary History 38.4 (2007) 739-753.

This article updates my sense of literary value: literature is language that exhibits dense internal interactions, as well as a great variety of interactions with its readers. “The sheer quantity and density of interactions are, in fact, exactly what make literature literature.” I like this formulation for now because it jives well with an ecological metaphor for human life: life is about expanding sociability through biodiversity, while good literature is about expanding communication through diversity of language, of artistry, of experience and imagination. Although I haven’t thought it through just yet, it seems to me that thinking of literature in this way gives us room to accept strong messages of advocacy as well as simply complex or realistic or otherwise sophisticated works of art.

Take Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring (1962) as an example, says Foote. This is a good book to choose because it illustrates how a book and its critics can affect the social and natural worlds: Silent Spring started a very large national conversation about the effects of trace poisons that involved a large and expensive effort by the chemical industry to destroy Carson’s legitimacy. Eventually Carson’s work triumphed, Carson became a heroine, and certain steps were taken to open a national conversation on the environment. More importantly, Carson left a major mark on the narrative tradition in coming up with a form that suited the new problems of her day. As John Haines would say, Carson followed the example of the great modernists of the early twentieth century in tailoring artistic form to the needs of the moment with a consciousness that art, history, the environment, and our humanity are all interrelated pieces of some whole.

Foote’s nice reading of the epigraphs to this book and to its opening lead her to an application of network theory as the metaphor for this model: “In the parlance of network theory, Carson wove together an extraordinary array of influences to create a compelling communicative ‘hub,’ an O'Hare or LAX for ideas and emotions to move through, launch from, and reference. Her creation has never since lacked for emotional and intellectual traffic.” Foote calls for New Historicism, New Criticism, New Media studies, Reader-response criticism and other aspects of modern theory to work together to explain exactly how Carson was able to create persuasive, contentious rhetoric that opened so many eyes to the perils of the environment, and that continues to do so. Implicitly, Foote also can be said to be asking us to study why Silent Spring also stirred strong opposition, how the story of Silent Spring has been transformed throughout its afterlife. We are also meant to ask what exactly made Silent Spring a success when similar texts like the 1960s environmental essays of John Haines, say, are ignored.

This last bit would trouble Haines, I think. I think many artists find something repugnant in trying to crack open the secrets to fame and influence. As artists, they are afraid what might happen to art if the passion to create is understood as a function of the desire for influence. And rightly so, I think; art that plans to have a big effect can’t, as a rule. Art must begin with a certain attention to the world, to the reality of life in the world, and not be distracted by any vision of the unpredictable effects that the art may have in the future. John Haines is uncomfortable with the term “vision,” and now I can see why. But for the critic and teacher, vision is absolutely necessary, because we must choose what is good, often quite before any other readers have done so. Can a good teacher become a good artist? Certainly a good artist might also possess what it takes to teach -- I’ve seen this myself. But I’m not nearly so sure whether Foote’s interaction model, and my feelings of thrall over it, might be the death knell for any attempt I could ever make at creating art. I thus reach a dilemma that must be as old as the idea of teaching literature: should I continue to develop critical ability and give up on art, give up on criticism and pursue art, or continue to try for a composite form of expression that answers specifically to what I need to say?

One clue to the solution of my own dilemma is Foote’s assertion that literary criticism take an accounting of itself in light of the grandest vision it may have of art and society in interaction:

The next step would be to map literary criticism not just onto, but into, this interactive model. Literary critics constitute, after all, one of the most influential audiences for literature, the key group shaping the presentation of literature as an institutionalized narrative tradition, primarily through scholarly publication and university teaching. What territory, what potential, what influence does literary criticism have already, and what will it choose to claim in coming years? As Robert Scholes, Gerald Graff, and John Guillory have most memorably shown, these boundaries are hardly stable, and literary criticism could sharply interrogate and substantially expand them without exceeding its legitimate grasp.As an institution of literature experts, we should be ashamed that we didn’t treat Silent Spring as a work of literature before. We didn’t teach any literature that worked seriously to change the world, because we have slowly but steadily relinquished any potential for literary criticism to change the world.

Here we come to another aporia in my current thinking. Should a smart person such as myself work to join an institution such as a university? If Silent Spring were not already considered literature, I could imagine one of my projects to have been to make students and teachers take Silent Spring seriously. But perhaps Silent Spring’s true power as a persuasive text is damaged by bringing it into the institution. Foote knows this is possible; certainly John Haines would see it as more than likely. We return to then to the idea that we must take a full accounting of why, how and what it is we are doing, and try to develop a vision (yes, Haines, a vision!) of where we need to go next. Foote has an elegant idea for an opening question:

Working further with the narrative interaction model, critics looking for appropriate lines of inquiry might ask: where in current and past societies are the interactions of narrative most dense, potentially or actually? Which narrative works provide linguistic hubs, hearthfires, for those interactions, and how do they do it? ... Where, though, are the constellations that literary criticism has missed?The interactive model allows us to spot the dense areas, and we must attend to those. But we also need to fill in the gaps, or at least understand why the gaps are there: Haines tells us that it is a tragedy more people haven’t heard of Edwin Muir or Hermann Broch. Is it? Why?

No comments:

Post a Comment